This is not an original article of invest-in-albania.org.

You may read the original one by clicking here.

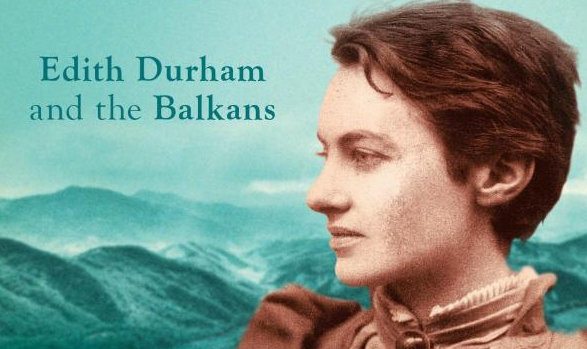

“God has sent you to save us,” read a message from the citizens of the town of Berat to Edith Durham, who arrived there in 1904, the first Englishwoman to set foot in that part of Albania. A traveller, writer and relief worker, she is still remembered in the country that she championed. In Albania’s Mountain Queen, Marcus Tanner traces her travels through the Balkans in the years preceding the First Word War, drawing on her writings and setting them against a historical background. The result is a vivid story of a woman and her time.

Born in London, Durham first visited the Balkans in 1900, already in her late thirties, and the trip proved a turning point in her life. It allowed her, instead of remaining a proverbial spinster, to establish herself as a prominent figure in the region. Not that the escape went smoothly: local men, bemused by her unmarried status, often proposed to her, until the people began worshipping her as a higher being, omnipotent and unsexed.

Within a few years, Durham, at first “just another lady traveller with an easel and a private income”, became an expert on “the Balkan tangle” and an active campaigner for justice, supporting the locals in their fight against Ottoman rule. She published seven books and numerous newspaper articles about the region, including reports from the First Balkan War. Her observations were usually sharp and devoid of moralising, often with a sarcastic finish: the Albanian provisional government, for instance, was described as a “Gilbert and Sullivan-looking body”.

Initially supportive of Serbia, Durham changed her allegiances with time. For a while she was on the side of Montenegro, having become close to its royal family, but her sympathy for Albania proved the greatest. After the country proclaimed its independence in 1912, Durham immediately realised that the question of borders would have to be solved and managed to alert the powers in London to the problem.

Durham’s perseverance was striking. During one particularly arduous journey across Albania, after a day’s riding in driving rain, she was offered a bed in a harem and had to stay in a barn full of onions. Being sceptical of religion, Durham came across various problems in the land whose Christian population had long been suffering under Muslims. Nurses in a Macedonian hospital who refused to feed patients during a fast were but one of the obstacles she encountered in her work. Distributing aid through her relief fund, she often felt close to despair – supplies were limited, people difficult to deal with – but always pulled through.

With her progressive views and independent character, Durham was ahead of her time in some ways, remaining its true daughter in others. She was accused of having “a pet Balkan people”, a charge Tanner thinks unfair, although he admits that “[s]he was sometimes bigoted towards entire nations”. Her other contradictions included contempt for women and a tendency to define justice in her own terms. Still, the fact that she “was not a plaster saint” makes her an even more fascinating figure. A century on, in our world of postcolonial studies, old prejudices still die hard. Now that Albania is about to be integrated into the EU, an account of its past is timely, especially coming from someone who was present at the country’s birth, loved it and tried to write about it with a cool head.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.